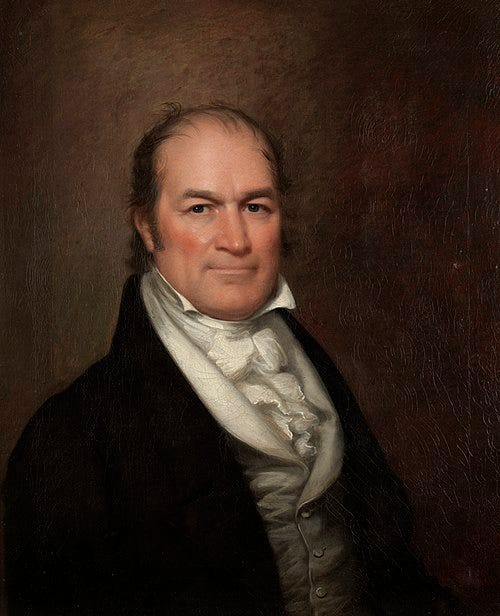

The Alternative Presidents of the Founding Era - Part 8 - William Harris Crawford

The American Founding Generation included some of the best presidential potential our nation has ever seen

William Harris Crawford (1772–1834) rose from the Georgia frontier to the very center of national power. Tall, blunt, and famously direct, he made his name first in state politics and then in the U.S. Senate, where he impressed friends and foes alike with his command of finance and his steady temperament. A duel in 1802 (he killed a rival) burnished a frontier-tough image, but beneath it was a calculating, competent mind. Madison tapped him for the Cabinet during the post–War of 1812 reconstruction—first at War, then as Secretary of the Treasury—where Crawford helped put the Second Bank of the United States on a practical footing and steered the government back toward solvency.

His virtues were those that wear well in a republic: fiscal honesty, administrative experience, a conciliatory streak across factions, and a preference for results over rhetoric. A Jeffersonian by creed but no dogmatist, Crawford believed in a limited federal government that still possessed the muscle to defend commerce, settle borders, and invest where the Constitution clearly allowed. The upshot: a leader both safe and able, with the stature to govern and the judgment to avoid expensive adventures.

The Election of 1816: Republican vs. “Independent Republican”

With the Federalists declining to field a ticket, the fight is inside the big tent. Crawford wins the Republican nomination; James Monroe bolts and runs as an Independent Republican, drawing on Virginia prestige and war-hero glow. Crawford campaigns on three planks—pay the debt, keep the peace, build what we need—and wins comfortably. He signals unity in victory: the government will be staffed for competence, not score-settling.

Cabinet (First Term):

State: John Quincy Adams (brains, languages, and a map in his head)

Treasury: William Lowndes (South Carolina’s calm financial mind)

War: John C. Calhoun (organizer, modernizer)

Navy: Benjamin Crowninshield (later Smith Thompson)

Attorney General: William Wirt

Bringing in J.Q. Adams is the tell: Crawford wants a quiet, professional foreign policy—firm, not flashy.

Foreign Affairs: Borders Settled, Seas Quiet

Great Lakes & the 49th Parallel. With Adams at State, the Rush–Bagot understandings (1817) keep warships off the Great Lakes; the Convention of 1818 fixes the 49th parallel to the Rockies and shares Oregon for the moment.

Florida Secured, Claims Cleared. Jackson’s hot pursuit of Seminole raiders forces the issue; Crawford backs Adams’s legal case that Spain can police the frontier—or cede it. The Transcontinental (Adams–Onís) Treaty (1819) brings Florida under the U.S. flag, settles a Pacific boundary, and cleans up claims—done as a ledger-balanced swap, not a swaggering land grab.

A Hemisphere Principle—Without Trumpets (1823). When Europe eyes intervention against Latin American revolutions, Adams drafts and Crawford signs a spare statement: no new European colonies or transfers in the Americas; in return, the U.S. won’t meddle in Europe’s quarrels. It’s essentially the Monroe Doctrine with the Crawford–Adams imprint—lawyerly, firm, and affordable.

Money, Credit, and the Panic of 1819

Crawford governs like the seasoned treasurer he is. The Second Bank is kept as stabilizer, not cudgel; customs and land sales fund the state; internal taxes are minimal and, where used, sunsetted. When the Panic of 1819 hits—land speculation pops, credit contracts—Crawford refuses both denial and drama:

Solvency first: interest paid on time; discretionary spending slowed, not slashed.

Measured support: the Bank is urged to act as a prudential lender of last resort, easing the worst pressure without inflating a new bubble.

Relief that’s rules-based: longer terms for smallholders on public-land debts; surveys accelerated so titles are clean and marketable; bankruptcy and debtor policies rationalized to prevent cascading ruin.

Tariff kept mainly for revenue: where protection is politically unavoidable, measures are narrow and temporary.

Recovery is messy but orderly—no embargo on common sense, no bonfire of institutions.

Internal Improvements: The Useful Middle

Crawford splits the difference between strict construction and national necessity. He vetoes blanket internal-improvements bills that lack constitutional hooks, but signs targeted projects tied to commerce, post, or defense:

National Road extended by stages, with federal–state cost sharing.

Rivers, harbors, lighthouses improved to lower insurance and transport costs.

Canal partnerships (Erie, Chesapeake–Ohio) via federal subscriptions rather than full federal ownership.

It’s the Gallatin map done the Crawford way: surveys before shovels, compacts before commitments.

Army, Navy, and the Frontier

Army: peacetime establishment trimmed to sanity, but staff work professionalized, arsenals maintained, and frontier posts kept credible.

Navy: cruising squadrons in the Caribbean and Mediterranean suppress piracy and protect trade; ships are built to last, not just to launch.

Indian policy: treaty obligations insisted upon; land frauds policed where the law reaches; the Army’s mission is peace-keeping, not provocation.

Missouri and the Union’s Balance (1820)

When the Missouri question explodes, Crawford spends political capital to back a lawful bargain: Missouri admitted as a slave state; Maine admitted free; slavery barred in the remainder of the Louisiana Purchase north of 36°30′. He neither gloats nor lectures. The message is plain: the Union is preserved by rules everyone can read and obey. The temperature drops; the scar remains, but the patient lives.

Politics & Temperament

Crawford is not a cult of personality. He runs the government like a serious shop: ledgers closed, correspondence answered, patronage used to bind regions, not punish enemies. Newspapers stay loud; he ignores most abuse and answers the rest with numbers. By 1820, he wins re-election with ease—the Era of Good Feelings with a bookkeeper’s backbone.

In the second term he finishes what he started: locks in boundary settlements, completes a wave of harbor and river improvements, normalizes a Navy that is visible enough to deter, small enough to pay for, and keeps debt on a downward glide.

What Eight Crawford Years Leave Behind

Credit unquestioned, debt trending down.

Borders tidied: Florida acquired, the 49th set, Oregon managed, Great Lakes quiet.

A working hemisphere rule stated with economy and backed by enough seapower to matter.

Infrastructure that pays for itself: roads, canals, lights, and river mouths that cut costs for farmers and merchants alike.

Panic weathered like adults: relief without wrecking the currency or the Bank.

Sectional fire contained—for a time—by compromise honored to the letter.

Bottom line: Crawford governs like what he is—the Republic’s most capable practical Jeffersonian. He spends political capital on solvency, surveys, and settlements; resists grandstanding; and leaves behind a larger, calmer, better-connected Union. If Monroe gave our history a doctrine with his name on it, this timeline gives us the same substance with a different author—and a presidency remembered less for rhetoric than for results that lasted.

Love this series, keep up the great work!

P.S. Have you thought about making top 10 lists of the best presidents, governors, senators, etc.?