Forgotten Democrats - Part 1 - John W. Davis

Constitutional Lawyer, the Last Conservative Presidential Democrat Nominee, and the Greatest Chief Justice of the 20th Century - that we should have had.

Forgotten Democrats: A Legacy of Lost Conservatism

The Democratic Party of 2025 is nearly unrecognizable compared to its historic self. With its fusion of corporate donorism, neoliberal economic orthodoxy, and cultural radicalism, the party now operates as a political machine that’s far removed from the values and priorities that once defined much of its membership.

It’s easy to forget that, for most of its history, the Democratic Party was home to patriots, constitutionalists, traditionalists, and moral reformers—men who, though not always aligned with modern conservatism, carried the torch of duty, discipline, and ordered liberty.

In this new series, Forgotten Democrats, we will recover the legacy of those figures—leaders and thinkers who stood for restraint, honor, and a pragmatic, commonsense approach to governance. They were men who, in another era, might have been Republicans, or perhaps more accurately, men who belonged to a time when party labels still allowed for real ideological diversity.

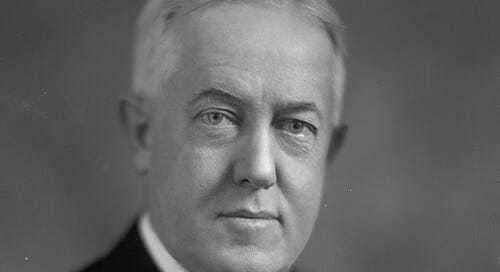

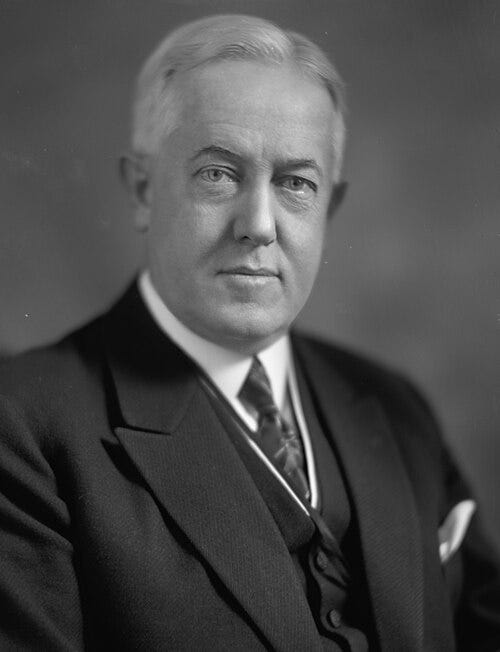

Our First Entry: John W. Davis

The Last Conservative Democratic Presidential Nominee

Our journey begins with John W. Davis, the 1924 Democratic nominee for President of the United States—a man whose dignity, intellect, and constitutional fidelity placed him firmly in the tradition of Jefferson and Madison.

Davis was no firebrand, no ideologue. He was a serious lawyer, a constitutional scholar, a man of deep principle and immense prudence. He believed in the balance between change and continuity, in upholding constitutional order against both radical reaction and reckless reform.

He was also, in many ways, the greatest Chief Justice of the 20th century that we never had. Though he never sat on the Supreme Court, Davis’s influence on legal thinking—and his record as an advocate before the Court—was immense. He was a strict constructionist before the term was fashionable, a judicial conservative who understood that law must reflect both principle and permanence.

John William Davis stands as one of the most intriguing figures in American political history. A consummate lawyer, diplomat, and politician, Davis's legacy is one that resonates deeply with themes of constitutional conservatism, states' rights, and a profound belief in the rule of law. Although often overlooked in contemporary discussions of American statesmen, Davis’s life and career exemplify the principles of a conservative Democrat, rooted in a time when the party harbored a wide spectrum of ideological stances. As the Democratic Party’s nominee for President in 1924, his defeat by Calvin Coolidge marked the end of an era, yet his influence persisted, especially in legal circles where he argued some of the most significant cases of the 20th century. This article will explore why John W. Davis was not only a conservative Democrat but also a great American statesman and constitutional conservative.

Early Life and Legal Foundation

John W. Davis was born in 1873, less than a decade after his state and the nation were torn apart by the Civil War, into a family with deep roots in West Virginia's political and legal landscape. His father, John J. Davis, was a prominent lawyer and a Confederate sympathizer during the Civil War, which exposed young John W. Davis to the complexities of American politics from an early age. After attending Washington and Lee University, Davis went on to study law at the University of Virginia School of Law, where he developed a profound respect for the U.S. Constitution and the principles of limited government.

Davis’s early legal career was marked by his deep commitment to the rule of law and the belief that the Constitution was the bedrock of American democracy. He returned to Clarksburg to practice law, where his skills quickly gained him a reputation as an exceptional attorney. His conservative beliefs were grounded in the idea that the federal government should be constrained by the Constitution, with powers not explicitly granted to it reserved for the states. This belief in states' rights and limited government would remain central to his political ideology throughout his career.

Entry into Politics: The Democratic Party and States' Rights

Davis’s entry into politics was almost inevitable given his family’s background and his own ambitions. In 1910, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as a Democrat from West Virginia. During his time in Congress, Davis aligned himself with the conservative wing of the Democratic Party, which was wary of the expanding powers of the federal government under the progressive agenda of Presidents like Theodore Roosevelt and later Woodrow Wilson.

As a Congressman, Davis advocated for policies that reflected his belief in limited government and states' rights. He was particularly concerned about the encroachment of federal power on issues that he believed should be decided at the state level, such as education, labor laws, and infrastructure development. Davis saw the Tenth Amendment, which reserves powers not delegated to the federal government to the states, as a crucial safeguard against federal overreach.

This commitment to states' rights was not merely a rhetorical stance for Davis but a deeply held belief. He feared that an overbearing federal government could erode individual liberties and the ability of states to govern according to the wishes of their citizens. This perspective placed him at odds with the more progressive elements within the Democratic Party, who were pushing for greater federal intervention in economic and social issues.

Diplomatic Service and Legal Mastery

Davis’s legal acumen and his adherence to constitutional principles did not go unnoticed by the political establishment. In 1913, President Woodrow Wilson appointed him as Solicitor General of the United States. In this role, Davis argued numerous cases before the Supreme Court, earning a reputation as one of the most skilled and persuasive advocates of his time. His tenure as Solicitor General further solidified his belief in a strict interpretation of the Constitution, where the judiciary’s role was to interpret the law as written, not to legislate from the bench.

In 1918, Davis’s career took a turn towards diplomacy when President Wilson appointed him as the U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom. During his tenure in London, Davis worked to strengthen the ties between the United States and the United Kingdom, navigating the complex post-World War I landscape. His diplomatic efforts were characterized by a pragmatic approach that prioritized American interests while respecting the sovereignty of other nations—a reflection of his constitutional conservatism on the international stage.

The 1924 Presidential Campaign: A Conservative Democrat's Last Stand

The pinnacle of Davis’s political career came in 1924 when he was nominated as the Democratic candidate for President. The Democratic National Convention of 1924 was one of the most contentious in American history, reflecting the deep divisions within the party between its conservative and progressive wings. After 103 ballots, the convention finally settled on Davis as a compromise candidate, largely because of his conservative credentials and his ability to unite the various factions of the party.

Davis’s campaign for the presidency was a clear articulation of his conservative principles. He ran on a platform that emphasized states' rights, limited government, and a strict interpretation of the Constitution. Davis was deeply concerned about the increasing centralization of power in the federal government, which he believed threatened the liberties of individual citizens and the autonomy of the states. His campaign speeches often echoed themes of constitutional conservatism, warning against the dangers of federal overreach and advocating for a return to the principles of governance laid out by the Founding Fathers.

One of the central issues of the 1924 campaign was the role of government in the economy. Davis opposed the idea of the federal government playing an active role in regulating business or intervening in the economy, arguing that such actions were beyond the scope of what the Constitution allowed. He believed that the best way to ensure economic prosperity was to allow states and local governments to address issues such as labor laws, business regulations, and infrastructure development according to their specific needs and circumstances.

Davis also took a strong stand on the issue of civil liberties, particularly the protection of free speech and the press. He was concerned about the growing tendency of the federal government to restrict these freedoms in the name of national security or public order. Davis argued that the Constitution provided clear protections for individual liberties, and that these protections should not be eroded by temporary crises or the whims of the majority.

However, despite his best efforts, Davis faced an uphill battle in the 1924 election. The political climate of the time was not favorable to a conservative Democrat, and he was up against the immensely popular Republican incumbent, Calvin Coolidge, who was seen as a steady hand during a period of economic prosperity. Additionally, the progressive wing of the Democratic Party was not fully behind Davis, leading to a lack of enthusiasm among many Democratic voters. In the end, Davis lost the election in a landslide, winning only 29 percent of the popular vote and carrying just 12 states, all in the South.

Legacy as a Constitutional Conservative

Despite his defeat in the 1924 presidential election, John W. Davis’s influence as a constitutional conservative did not wane. He returned to private practice and became one of the most respected lawyers in the country, arguing numerous cases before the Supreme Court. His most famous case was Brown v. Board of Education (1954), where he represented the state of South Carolina in its defense of school segregation. Although Davis lost the case, his arguments were a reflection of his belief in states' rights and his conviction that the Constitution should be interpreted according to its original meaning.

Davis’s role in Brown v. Board of Education has been a subject of controversy, with some critics viewing his defense of segregation as a stain on his legacy. However, it is important to understand Davis’s actions in the context of his broader commitment to constitutional principles. For Davis, the issue was not about the morality of segregation, but about the proper role of the federal government and the judiciary in determining social policy. He believed that such decisions should be left to the states and their citizens, not imposed by the federal government.

This stance was consistent with Davis’s lifelong commitment to a strict interpretation of the Constitution. He viewed the Tenth Amendment as a crucial safeguard against federal overreach, and he feared that a broad interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment could lead to an erosion of states' rights. While his views on segregation were undoubtedly shaped by the racial attitudes of his time, Davis’s legal arguments were rooted in his belief that the Constitution should be interpreted as it was originally written, with any changes to its meaning coming through the amendment process rather than judicial fiat.

Davis’s commitment to constitutional conservatism extended beyond the issue of segregation. Throughout his career, he argued against the expansion of federal power in areas such as labor regulation, business oversight, and economic intervention. He believed that the federal government’s role should be limited to the powers explicitly granted to it by the Constitution, with all other powers reserved for the states. This belief put him at odds with the more progressive elements within the Democratic Party, but it also earned him the respect of conservatives across the political spectrum.

A Great American Statesman

John W. Davis’s legacy as a great American statesman is not just rooted in his political and legal achievements, but also in his unwavering commitment to the principles of constitutional conservatism. He was a man who believed deeply in the importance of the rule of law and the need to protect individual liberties from the encroachments of an overbearing federal government. His views were shaped by a reverence for the Constitution and a belief that it provided a framework for governance that balanced the needs of the nation with the rights of the states and individuals.

A Man of Principle, Not Party

Davis broke with his own party more than once—most notably when it veered too far from constitutionalism. Though he supported limited social reform, he opposed federal overreach and rejected the growing trend of courts as engines of social transformation.

He believed the Constitution was not a blank slate to be reinterpreted with every political whim, but a framework of ordered liberty, requiring discipline from both the governed and those who govern.

Had his approach prevailed in the critical legal battles of the 1950s—particularly in debates over judicial activism—the course of American history might have been profoundly different. The cultural upheaval and institutional chaos of the 1960s and 70s, which still haunt us today, might well have been softened or avoided altogether.

Why Davis Matters Today

In an age of hyper-partisanship and moral relativism, John W. Davis stands as a rebuke to both the woke left and the shallow populism of some elements on the right. He reminds us that conservatism is not a posture or a slogan—it is a temperament. A way of seeing the world that values duty over drama, law over passion, and legacy over momentary applause.

He was the last serious conservative to carry the Democratic banner on a national ticket. And for that alone, he deserves to be remembered.

Recommended Reading